Building Back Better after COVID-19 – Reimagining the Construction Sector

| Shankar Venkateswaran | 5 Min Read

One of the many faultiness that COVID-19 has exposed is the plight of migrant workers. Estimates vary on how much there are – all guesstimates because there is no hard data – but it can be safely assumed to be around 100 million. We also know that they are employed in a wide range of sectors but we do know that a significant number – one estimate suggests 40% – are employed in the construction sector, which is India’s second largest employer after agriculture.

Construction includes a range of buildings, factories, roads, flyovers, bridges, metros and so on being built. It also evokes images of huge cranes, cement mixers, pneumatic tools, scaffolding, road rollers and what have you. All this is of course true but these images often dwarf the large number of people, not all wearing safety equipment, engaged in hard manual labour in the heat and dust of a construction site. What is even less visible is how all the material that go into construction is produced and, more importantly, the people who produce them.

This piece speaks to the seamier human side of the construction industry which, like so many things in India, is known but ignored. It is about those whose horrific lives subsidise our fancy apartments and the infrastructure that we love complaining about. And, more importantly, it is about how COVID 19 potentially provides us the possibility to build back better.

Construction material – looking beyond cement and steel

In terms of material, cement and steel are very significant inputs of the built environment. But if you follow the debates, you may be forgiven if you are given the impression that there is little else to worry about. Cement and steel are capital and technology intensive and hence produced by large companies and once worker safety issues are taken care of, which one would expect in large companies, so are the human elements. The focus therefore is on the environment – reducing emissions, effluents and waste, eliminating fossil fuel use in the process, using renewable electricity etc.

But there is much more than steel and cement that goes into the construction – clay bricks, aggregates, grit, sand to name a few. Most of these are produced in the unorganised sector where, by definition, there is no security of wages, conditions of work are dangerous and where human rights is followed in breach.

Let’s start with bricks. Modern building techniques are slowly reducing the use of clay bricks but there is still a significant amount of it produced and used. Just drive around the villages surrounding any Indian town or city and you will the see stacks or chimneys which is the sure give-away that it is a brick kiln. One estimate says there are over 1.5 lakh brick kilns in India employing over 10 million workers. Clay brick manufacturing has to be one of the most primitive processes in use and, tragically, is where child labour and bonded labour is still prevalent. Typically, these bricks are produced by migrant labour in units of 3: a man, a woman and a child. The roles for each are clearly defined with the child’s role being to move between rows of wet bricks laid out to dry in the sun and turn them over – you need small feet for that and so children are irreplaceable! The workers just earn enough to eat – the rest being taken away by the middlemen to be set off against monies advanced to the families before they migrated. One estimate is that the wages paid to the workers is less than 5% of the retail price of the brick. Less said of the working conditions the better – the workers are undocumented (which eliminates all liabilities in case of accidents or death), safety is not on anyone’s mind and forget about working hours, adequate water, shade etc. And if the social conditions are not bad enough, bricks are made using precious top soil which is then lost forever!

The next in line is stones. Here, there are two varieties – coarse aggregates that, along with cement and sand, constitutes concrete and hence used in practically all construction. And the other is the decorative ones – marble, granite etc. – used for floors, wall tiling etc. Both these are mostly sourced from stone quarries, most of which is in the unorganised sector and, like bricks, made by the blood, sweat and tears of migrant workers. And apart from horrific work conditions that are like in brick kilns, stone quarries add another dimension to this grisly story – silicosis – a disease that people working in stone quarries get by inhaling fine particles of silica from stone that is known to cause lung infections, heart failure, cancer, disability and premature death!

The people

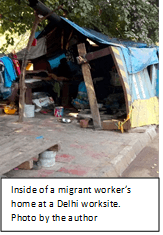

The built environment then has to be built. You are right if you think that a lot of these are built by large, hi-tech construction companies who must be taking care of the human element. And though increasingly a lot of these structures come semi-finished from a factory, someone must tie the steel rods for the columns, someone has to carry bricks and material to structure and so on. The large companies, whose shares you and I own, outsource these tasks and it is back to the old familiar middle-man – of the same ilk as those who “supply” labour to brick kilns and quarries – who sources manual labour from villages and brings them to the worksite. And here again, they live in unhygienic shanties near the worksite, their children running around supervised by the elder sibling – usually the girl – who drop out from school. Next time you drive by an apartment building or a highway under construction, just park your car somewhere and take a look at who is working there and how they live. Or speak to folks at Mobile Creches, an NGO working for child rights at construction sites, and they will show you a thing or two. Warning – some scenes may be graphic and unsuitable for the weak-hearted!

It has to be said that conditions at worksites have improved significantly with workers being provided safety gear like helmets, masks and harnesses etc. However, the safety equipment is often ill-suited to the Indian summer and it at times causes so much heat that the already under-nourished worker runs the risk of heat strokes. Also, so little is invested in training workers on safety that accidents are no surprise, sometimes even undocumented because the workers themselves may not be recorded on a muster roll.

So, how do we build back better?

As we start reopening the Indian economy, especially the construction sector, the choice simply is do we revert to business-as-usual – which is the simpler option – or do we use this opportunity to build back better? Let’s also be real – even if we want to build back better, it is not going to happen overnight. Also, we must remember that those who can change things may not want to and those who want to – mainly the workers themselves – cannot! So, what needs to happen?

As with every problem, the first thing is for everyone – policy makers, policy enforcers, infrastructure builders, buyers, house owners – to acknowledge that we have a problem because if we don’t do that, all our so-called Smart Cities and highways will be built the same way as the Taj Mahal! Apart from a handful of NGOs and the odd mention by mainstream media (ironically, it was the BBC that ran a campaign on the state of brick-making called Blood Bricks), there is little coverage of this issue.

The construction industry is of course best placed to ensure that we build back better. The low-hanging fruit is of course what happens at the worksite and this is where they need to look beyond their tier 1 contractor to every sub-contractor down the line. They must ensure that every labour contractor is thoroughly audited so that they do not employ any form of forced or involuntary labour, that there are adequate budgets for safety training and refreshers on site and that the staying arrangements meet basic standards. If the company does not have its own standard, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) has a set of performance standards and of particular relevance is Performance Standard 2 for labour. I have seen the worksites of Tata Housing and while there is room for improvement, I have not seen a better run construction site and so, it is possible! An excellent role model that Indian construction companies can adopt is the Considerate Constructors Scheme of the UK, set up as a non-profit by the industry to promote practices that go beyond compliance.

Apart from construction sites that meet proper human rights standards, construction companies must also focus on the supply chain, right down to where the bricks, aggregates and flooring stones are procured. Since they are such large buyers of these material, they can significantly influence their suppliers; it will not enough to tell them to pay proper wages and provide clean and safe working and living conditions but to also ensure it. This, admittedly, will take time to change but post-COVID is the best opportunity to begin this process.

Companies that have plans to construct a new plant or office building post COVID too can play a significant part in building back better. They can do this by simply ensuring that they contract this out to construction companies who conduct themselves responsibly and ensure that this is followed in practice. Again, the IFC Performance Standards mentioned above provide guidance on how this can be done.

Government of course has a huge role to play. The obvious one is as a part of its regulatory role – developing building codes, standards and regulations with a strong grievance redressal system that enables swift action when these are breached. Beyond this, as arguably the entity with the largest construction budget in the country, it could contract only those that commit to responsible construction practices and put strict conditionalities on its contractors

Finally, what should we as individuals do? As consumers buying a house or an office, the first question we need to ask ourselves is how responsible is the builder in terms of his building and procurement practices. In some cases, it might mean paying a bit extra but change sometimes costs. If we are building our own house, then we need to set down some ground rules with our contractor – in terms of wages, work and living conditions on the site, safety, child labour and – this is admittedly difficult at an individual level – the sourcing of the material apart from cement and steel. Even while procuring cement and steel, we can well indicate which brands to buy based on our own assessment of which companies we might consider responsible. As employees of companies that are in construction or those that are procuring construction services, we can ask the right questions of our colleagues: Do we have policies that deal with workplace conditions? Do we have policies on sustainable and ethical sourcing? And, very importantly, do we have systems and processes that ensure that these policies are practised? And finally, as advocates and activists, we can join movements and campaigns that demand better behavior from companies, especially in regard to labour practices.

Written by Shankar Venkateswaran, Operating Partner & Head ESG, ECube Investment Advisors. The views expressed here are personal.